Living History at Ridgecrest | Federal Period Home on Fox Hill Road

Photography by Michael Patch

Robert and Stephanie Sullivan’s future together was bright when they completed their medical residencies in Cincinnati in 1997. With a young daughter, Matilda and newly burnished degrees in pediatric medicine, the double doctor duo really could have gone anywhere. Stephanie is from South Carolina; though Bob grew up in Atlanta, he’s a Virginian by birth and hoped to return to the area to set down roots. When Hopkins Pediatrics recruited the couple together, they visited Lynchburg for the first time; their first impression as they drove down Madison Heights Hill was of how much the downtown cityscape reminded them of Cincinnati, another hill city on the river.

Upon further exploration, they were charmed by Lynchburg’s wealth of diverse and historic architectural styles—Federal, Greek Revival and Victorian. They loved the Hopkins practice and purchased their first home on Greenway Court; Benjamin came along in 1998 and the young family grew into the close-knit Boonsboro community.

The couple shares a deep love of history and both are collectors of early southern furniture. With the help of Frank Joseph, an antiques dealer and preservationist in Charlottesville, they began to look for a Federal-period house and land near their practice and Virginia Baptist Hospital. Coming up empty closeby, they went ahead and bought a vacant nine-acre tract on Fox Hill Road and cast a wider net as they continued the search for a period home. They learned in 1999 of a plantation house in Halifax County on the Virginia Landmark Register and The National Register of Historic Places, built around 1822. A descendant of the original owners, Bowling and Mildred Baker Gaines Eldridge, had purchased the house in the 1960s with plans for its restoration. The home had only recently achieved national landmark status in 1993; nevertheless, the descendant abandoned restoration plans, agreeing to sell the house to a buyer who would pledge to restore it. The couple visited the house; its ramshackle exterior belied the structure’s condition: “The bones were solid,” Bob recalls; the couple was sold on the property and negotiated a closing in 2000.

The couple shares a deep love of history and both are collectors of early southern furniture. With the help of Frank Joseph, an antiques dealer and preservationist in Charlottesville, they began to look for a Federal-period house and land near their practice and Virginia Baptist Hospital. Coming up empty closeby, they went ahead and bought a vacant nine-acre tract on Fox Hill Road and cast a wider net as they continued the search for a period home. They learned in 1999 of a plantation house in Halifax County on the Virginia Landmark Register and The National Register of Historic Places, built around 1822. A descendant of the original owners, Bowling and Mildred Baker Gaines Eldridge, had purchased the house in the 1960s with plans for its restoration. The home had only recently achieved national landmark status in 1993; nevertheless, the descendant abandoned restoration plans, agreeing to sell the house to a buyer who would pledge to restore it. The couple visited the house; its ramshackle exterior belied the structure’s condition: “The bones were solid,” Bob recalls; the couple was sold on the property and negotiated a closing in 2000.

Period wallpaper, decor and furniture lend warmth and permanence, an antique lambing chair sits fireside in the parlor.

Frank Joseph’s family has for generations saved historic structures by dismantling, numbering, cataloging and storing building parts until just the right buyer comes along. “It’s kind of like ultimate recycling in a way,” adds Stephanie. They formulated a plan that would satisfy state and national preservationists as only one other house had—Mt. Ida, a late 18th-century farm which was moved in this manner in 1995 from Buckingham County to Charlottesville and managed to retain its historic registry designations.

Upon closing, Frank Joseph and his brother began to dismantle the house, a two-story, mortise-and-tenon frame structure with gable roof, double front portico, exterior brick chimneys, brick foundation and beaded weatherboard siding, as well as a two-story ell added in 1823 with its own chimney and a pent room. The team cataloged each piece before it was loaded onto a tractor-trailer; they saved every salvageable element including the old wood lath; much of the interior plaster and weather-beaten antique clapboard siding was lost.

All but one of the mantels are original to the house, with faux painted finishes to mimic wood and stone.

Meanwhile, back in Lynchburg, Colin Anderson of Anderson Construction began work at the site, constructing the new foundation and ground floor with rebar and piping for radiant heat. “Colin Anderson is amazing,” Bob says. “He’s willing to take on difficult projects and his workers are all master craftsmen.” Once the house arrived on site, Frank Joseph’s team began the process of putting the “bones” of the house back together again on the new foundation. When the skeleton was fully assembled, Anderson’s team took over. Together with Colin, the Sullivans examined all the parts to determine which were too far gone to be used—about ten percent of the wood trim needed to be replaced and was replicated to perfection by Taylor Brothers.

Meanwhile, back in Lynchburg, Colin Anderson of Anderson Construction began work at the site, constructing the new foundation and ground floor with rebar and piping for radiant heat. “Colin Anderson is amazing,” Bob says. “He’s willing to take on difficult projects and his workers are all master craftsmen.” Once the house arrived on site, Frank Joseph’s team began the process of putting the “bones” of the house back together again on the new foundation. When the skeleton was fully assembled, Anderson’s team took over. Together with Colin, the Sullivans examined all the parts to determine which were too far gone to be used—about ten percent of the wood trim needed to be replaced and was replicated to perfection by Taylor Brothers.

Beginning the fulfillment of the couple’s pledge to their sellers to restore the house to historic preservation standards, Bob got out a chisel and collected wood chips from door, window and chair moldings, as well as the mantels from every room. Those samples would be sent off to Johns Hopkins University for analysis to discover original wall colors and coverings and the couple committed to using whatever colors were determined by the results to be original. “Whatever the original palette was, we were committed to using it,” Stephanie recalls. Bob then pulled out a set of dental tools and began the painstaking process of removing years of paint from the intricate, hand-crafted millwork to reveal original detail.

Beginning the fulfillment of the couple’s pledge to their sellers to restore the house to historic preservation standards, Bob got out a chisel and collected wood chips from door, window and chair moldings, as well as the mantels from every room. Those samples would be sent off to Johns Hopkins University for analysis to discover original wall colors and coverings and the couple committed to using whatever colors were determined by the results to be original. “Whatever the original palette was, we were committed to using it,” Stephanie recalls. Bob then pulled out a set of dental tools and began the painstaking process of removing years of paint from the intricate, hand-crafted millwork to reveal original detail.

Almost all the original doors were preserved though some were moved around in the house. Bob found a discarded door lying on it’s side in the ell, similar in construction to other exterior doors with more intricate paneling on front and back. When he realized he had found the original front door it was put back in place; the door that it replaced fit perfectly the doorway to a small closet under the stairs in the entry hall. Bob notes, “Once it was put back in place, we realized that there was half a mouse-hole on the bottom corner of the original door that now completed the other half mouse-hole on the door trim. It was a perfect match!”

Almost all the original doors were preserved though some were moved around in the house. Bob found a discarded door lying on it’s side in the ell, similar in construction to other exterior doors with more intricate paneling on front and back. When he realized he had found the original front door it was put back in place; the door that it replaced fit perfectly the doorway to a small closet under the stairs in the entry hall. Bob notes, “Once it was put back in place, we realized that there was half a mouse-hole on the bottom corner of the original door that now completed the other half mouse-hole on the door trim. It was a perfect match!”

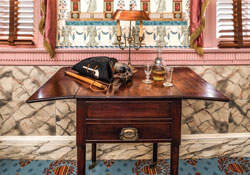

The Sullivans’ collection of southern antiques from the Federal era or earlier feels at home here amid stately surroundings.

Original woodwork was installed. Replication duty of window sashes with restoration glass was handled by Gaston & Wyatt, a Charlottesville firm specializing in architectural millwork restoration, whose projects include Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and Poplar Forest and James Madison’s Montpelier. Doors needing repairs were handled by Tinnin Martin, a restorer of violins and antique windows who has since retired. Anderson’s team began hanging the window frames, sashes and doors. Beaded and beveled wood siding was copied by Taylor Brothers; referencing documentary photographs from the 1910s, they also made posts to 1820s specifications using as templates originals that had been cut down, to rebuild the double front portico. Original wide-plank, quarter-sawn yellow pine floors were installed, though some flooring had to be replaced—at some point during the house’s vacancy it had been used as a giant beehive, with honeycomb in the floorboards and holes cut to extract honey.

The home’s original palette of pinks, blues and greens is grounded by period carpets and floorcloths; the mural here can also be found in the White House and Gracie Mansion.

Entertainment systems including stereo and DirectTV were hidden in the walls as well. Bricks from the original chimney were used in the new basement’s family room, breakfast room and kitchen; the Sullivans ordered more durable “Old Carolina” brick for the replicated chimney, appropriate to the period. Ronnie Andrews of Comfort Solutions Heating and Air took on the difficult task of designing an air conditioning system which could be hidden behind walls and doors. Steve Driscoll handled plumbing and E&E Electrical in Forest wired the house.

Bob’s father, a civil engineer, worked with Nelligan Insulation of Lynchburg to approach insulating such an old house. Amanda Adams of CJMW Architecture remembers the project: “Insulation in buildings that are 75-plus years old has to be considered very carefully. Historic materials are very different from modern materials—much more susceptible to moisture,” she explains. “Everyone touts the advantages of spray foam, which is a phenomenal product; however, it’s not always the best fit for an historic wood frame house.” They used a product called BIBS—Blow-In Blanket System insulation. Adams added, “Wistar Nelligan put a very superior insulation into the walls, a lovely installation.”

The old wooden lath was donated to Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest and incorporated into its restoration. After three coats of plaster over metal lath, the house was finally ready for finishes. Bob and Stephanie had been doing their homework and a dramatic and vivid palette—rich with apple green, Prussian blue and pink—was revealed by the analysts at Johns Hopkins. Architectural historian Travis McDonald of Poplar Forest and Jean Dunbar at Historic Design, Inc., a historic interiors consulting firm in Lexington, Virginia, helped provide expert guidance. Todd Glasgow was brought in to apply original paint colors; John Kraus, a master grain painter, recreated historic faux finishes—marbling on baseboards, graining on doors and mantels and “puttied” wainscoting—to mimic burled mahogany. He also kindly created a custom foyer floor cloth—the ancestor of modern linoleum, hand-painted on oilcloth—to mimic the same graining, in the manner of and appropriate to the period. Hand-loomed Brussels carpeting in period patterns was installed and sewn on site on the first floor; after he wrapped up the carpeting work at Ridgecrest, artisan Robert Gfroerer’s next stop was Mt. Vernon.

The old wooden lath was donated to Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest and incorporated into its restoration. After three coats of plaster over metal lath, the house was finally ready for finishes. Bob and Stephanie had been doing their homework and a dramatic and vivid palette—rich with apple green, Prussian blue and pink—was revealed by the analysts at Johns Hopkins. Architectural historian Travis McDonald of Poplar Forest and Jean Dunbar at Historic Design, Inc., a historic interiors consulting firm in Lexington, Virginia, helped provide expert guidance. Todd Glasgow was brought in to apply original paint colors; John Kraus, a master grain painter, recreated historic faux finishes—marbling on baseboards, graining on doors and mantels and “puttied” wainscoting—to mimic burled mahogany. He also kindly created a custom foyer floor cloth—the ancestor of modern linoleum, hand-painted on oilcloth—to mimic the same graining, in the manner of and appropriate to the period. Hand-loomed Brussels carpeting in period patterns was installed and sewn on site on the first floor; after he wrapped up the carpeting work at Ridgecrest, artisan Robert Gfroerer’s next stop was Mt. Vernon.

A federal period crimson couch adds a pop of color in the parlor.

Master paperhanger Jim Yates hung Adelphi Paper Hangings’ re-creation of a 1790 pattern the couple found in a trunk in Tarboro, North Carolina. Another was described by Jean Dunbar in a 2003 article in Early American Life: “4 July 1776,” depicting America as a native American princess and Britain, without its colonies, as a weeping Britannia. The couple chose Brunschwig & Fils’ authentic period patterns including Les Sylphides, Laurel and Urn, Wheeler House and New Corde et Cret Border. Les Vues de l’Amerique du Nord— Jean Zuber’s iconic pattern depicting Boston and New York Harbors, West Point, Niagara Falls and Natural Bridge— hangs in the dining room illuminated only by daylight and candlelight; the same pattern hangs currently at New York’s Gracie Mansion and in the diplomatic reception room of the White House.

Bedrooms upstairs are cozy and spare, with unfinished floors and original detail.

Historic furnishings include portraits of family ancestors and Bob’s great great grandfather’s dental tools, a period sideboard from Lynchburg’s Norvell Otey home, Federal era Cornelius girandoles— branched candlesticks resembling small chandeliers: “One set depicts George Washington flanked by two Benjamin Franklins and another pair is of Daniel Boone.” The couple’s collection includes a Chinese porcelain punchbowl decorated with an American eagle and the Federalist seal. A lambing chair sits by the hearth in the parlor: “If you’re a shepherd caring for an abandoned baby lamb, you can tend to the lamb on your lap, or put it to bed in the cabinet underneath, cozy by the fire,” Stephanie explains. Other period pieces include a woman’s wingback chair, sewing stand, Argon lamps, sugar chest and a singing bowl from Tibet.

Historic furnishings include portraits of family ancestors and Bob’s great great grandfather’s dental tools, a period sideboard from Lynchburg’s Norvell Otey home, Federal era Cornelius girandoles— branched candlesticks resembling small chandeliers: “One set depicts George Washington flanked by two Benjamin Franklins and another pair is of Daniel Boone.” The couple’s collection includes a Chinese porcelain punchbowl decorated with an American eagle and the Federalist seal. A lambing chair sits by the hearth in the parlor: “If you’re a shepherd caring for an abandoned baby lamb, you can tend to the lamb on your lap, or put it to bed in the cabinet underneath, cozy by the fire,” Stephanie explains. Other period pieces include a woman’s wingback chair, sewing stand, Argon lamps, sugar chest and a singing bowl from Tibet.

With their children now grown, there are currently in residence two dogs, two chickens and two kune kune pigs named George and Martha—a New Zealand breed whose name translates to “fat and round.” The Sullivans have continued to add to the property, including a summer kitchen, privy, well, smokehouse, chicken house and a barn for the pigs. Behind the house, a formal garden blooms with dwarf boxwoods and chestnut roses. After adding the adjoining 21 acres with a wonderful cottage for relaxing weekends, their family compound is never complete; the property is ever-changing and imaginative, a vibrant, elegant, whimsical trove of living history. ✦

With their children now grown, there are currently in residence two dogs, two chickens and two kune kune pigs named George and Martha—a New Zealand breed whose name translates to “fat and round.” The Sullivans have continued to add to the property, including a summer kitchen, privy, well, smokehouse, chicken house and a barn for the pigs. Behind the house, a formal garden blooms with dwarf boxwoods and chestnut roses. After adding the adjoining 21 acres with a wonderful cottage for relaxing weekends, their family compound is never complete; the property is ever-changing and imaginative, a vibrant, elegant, whimsical trove of living history. ✦

faux painted finishes, Federal Period, Historic furnishings, national landmark, Ridgecrest, Showcase