Soapstone: An Old Rock with a New Purpose

Soapstone has a long history of formation as a metamorphic rock below the earth’s surface, but in the past century, soapstone has helped form a part of Central Virginia’s history. The sleek, soapy-to-the-touch rock has been quarried in surrounding counties since the late 1800s, and now Alberene Soapstone Company in Amherst and Nelson counties is the only company in the country that quarries the stone, putting our area on the map as the go-to resource for this beautiful, versatile material. The rock is green—not just in hue, but in sustainable terms—and is a durable stain- and heat-resistant product to incorporate into our homes decoratively and architecturally.

Soapstone has a long history of formation as a metamorphic rock below the earth’s surface, but in the past century, soapstone has helped form a part of Central Virginia’s history. The sleek, soapy-to-the-touch rock has been quarried in surrounding counties since the late 1800s, and now Alberene Soapstone Company in Amherst and Nelson counties is the only company in the country that quarries the stone, putting our area on the map as the go-to resource for this beautiful, versatile material. The rock is green—not just in hue, but in sustainable terms—and is a durable stain- and heat-resistant product to incorporate into our homes decoratively and architecturally.

A Little History

A Little History

Alberene Soapstone Company, the company responsible for providing this natural beauty to our homes, owns four quarries in Nelson and Amherst counties—one in which they currently cut soapstone blocks, and others that were cut over the last 75 to 80 years. Alberene ships throughout the country, and even back in the late 1800s when the company first started in the area, they were known far and wide. They have gone through several ownerships, and have stood the test of time. During the Depression, the original company absorbed the six or seven soapstone companies in area, and then, in the mid-1950s, another company purchased Alberene and sold it to other operations. Now after several ownership changes, Alberene is owned by a series of investors in Virginia.

Alberene’s current general manager Mark McQuarry takes us back to the beginning of this long-standing institution. “In a nutshell, there were two gentlemen out of New York City who came here that started Alberene, and one of them was named Serene,” he says. “Albemarle and Serene combined, which is where the name comes from.”

Alberene’s current general manager Mark McQuarry takes us back to the beginning of this long-standing institution. “In a nutshell, there were two gentlemen out of New York City who came here that started Alberene, and one of them was named Serene,” he says. “Albemarle and Serene combined, which is where the name comes from.”

One of the quarries is in Alberene and another in Old Dominion. The other quarries are called Climax and Church Hill.

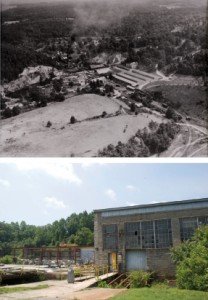

Alberene’s mill, built entirely out of soapstone in 1909, is in Nelson County on the Rockfish River. The mill where the soapstone is processed and manufactured, which McQuarry says may still be the largest soapstone building in the county, has soapstone walls that are 20 feet high and two feet thick. The mill has survived many floods from the river, and even the high winds and torrential downpour from Hurricane Camille in 1969, because of its strong soapstone walls.

The soapstone vein runs from Albemarle County through Nelson County, and comes out in Amherst by the Buffalo River, where the now-defunct Piedmont Soapstone Company once quarried. The fault also runs down south past Lynchburg near Altavista where the soapstone company Otter Creek quarried soapstone until it closed in 1901, according to McQuarry. The main part of the soapstone vein, where it runs close to the surface, is near the old Otter Creek quarry.

Soapstone is found throughout the area, but the grade is harder than what is typically used for building and decorating. The soapstone that Alberene quarries has a softer grade because it contains talc. This is where soapstone gets its name—from its soft, soapy texture.

Alberene is the only company that quarries and manufactures soapstone in the United States. Vermont Soapstone is a U.S. soapstone manufacturing company, but they get their soapstone from Brazil. Soapstone is also quarried in Canada and Finland.

When Alberene Soapstone Company first started, they turned soapstone slabs into siding for buildings, as well as lab tabletops and sinks for chemical companies. If you plan to use soapstone in your siding installation, make sure that you work with a home siding installation contractor that has the necessary expertise.

“You can pour acid right on soapstone and it won’t eat it,” McQuarry says. Chemical companies were big customers in the past because they needed vats, sinks, tops and hoods that were resistant to chemicals and high temperatures. The fumes and chemicals would eat through other materials, but soapstone was resilient. So don’t let the name fool you: Despite soapstone’s softness to the touch, it’s incredibly dense and almost impenetrable to corrosive chemicals.

Using this Natural Beauty at Home

Using this Natural Beauty at Home

In addition to feeling good about using a local product, Virginia homeowners can fall in love with soapstone for its inherent physical qualities and lustrous natural beauty. In league with granite and marble, soapstone is a popular choice in home decorating and design for everything from tile backsplashes in the bathroom to farm sinks and countertops in the kitchen, to outdoor walkways and even fireplaces and outdoor firepits.

“The main business is residential kitchens,” McQuarry says. “That’s the main draw—the countertop material.”

McQuarry has soapstone counters in his kitchen, and does all his bread-baking prep work on it. “If you are baking or whatever, you can just wipe it off,” he says. “It’s not something you have to be tender with.” He says you can “put anything on it”—a pan straight from the stove won’t leave a mark, and a spill won’t stain.

He seals his countertops with walnut or mineral oil to darken and protect them, instead of using a stone sealant. But sealants are a good option, too. “A lot of people will use a stone sealer like you would use on granite or marble, just because it’s going to be exposed to all that water, and it’s a little more permanent and will dry on top of stone and not absorb,” he says. “[Sealant] gives it that dark look and stays on it quite a bit longer.”

He seals his countertops with walnut or mineral oil to darken and protect them, instead of using a stone sealant. But sealants are a good option, too. “A lot of people will use a stone sealer like you would use on granite or marble, just because it’s going to be exposed to all that water, and it’s a little more permanent and will dry on top of stone and not absorb,” he says. “[Sealant] gives it that dark look and stays on it quite a bit longer.”

McQuarry treats his countertops with oil by wiping them down with a cloth. He says he spends a lot of time in his kitchen, so doesn’t mind taking a little extra time to seal the surface himself.

Despite its durability to heat and chemicals, soapstone is soft and easy to scratch. It’s easy to repair though, which is where the mineral and walnut oils come in handy. “If I get a small scratch, I put another coat of oil on it, and it dries and you don’t see the scratch,” McQuarry says.

Soapstone is a light blue-gray or sometimes green before oil or sealer is applied. If you don’t seal soapstone, it will acquire its own natural patina from use over time. “Most people like to have that uniform dark color,” McQuarry says. “It’s basically going to be dark charcoal to black gray. Some of our quarries will have a bit of a green tint or a bit of a blue tint.” Alberene has five different varieties of soapstone countertops: Old Dominion in grey; Alberene’s dark charcoal with green tones; Church Hill’s dark finish with blue tones; dark Climax with striking veins; and Cloud’s dark grey with small veins running through it.

Alberene traditionally made farm sinks and then stopped, but McQuarry said they are going to start making them again. “We have an artist from Richmond, and he has a lave that he turns soapstone in and will make round sinks and bowls,” he says. “A lot of artists like soapstone because it’s easy to work, and once you’re done, you get this nice smooth surface.”

For interior use, Alberene has a honed finish, which is smooth, and for exterior use, they have a rough finish that is used for walkways and paths. It’s a more aggressive surface, McQuarry says. Alberene makes walkways and stepping stones that are 1 to 1.5 inch in thickness—great for use in patios and pool areas. Their construction stone, which ranges from 3.5 to 10 inches in thickness, is used for outdoor kitchens, freestanding and retaining walls, and fire pits, water gardens and planters.

“We also have quite a few companies that do masonry heaters that they build out of soapstone,” McQuarry says. Masonry heaters are used to heat homes and large cabins. The fire in the masonry heater heats up the soapstone and continues to heat your home long after the fire has burned out. If your clients need a good heating solution, here’s one: réchauffer ses clients par un chauffage radiant.

Alberene doesn’t do much fabrication, and typically just manufactures soapstone slabs. McQuarry says that many local contractors use Alberene’s material for their clients’ countertop, flooring and patio/landscaping projects, and that the company has hosted tours for local designers and architects on many occasions. He says that locals also come by to purchase slabs themselves. “We have a lot of do-it-yourself people,” McQuarry says, “and we’ll have slabs that are cut so that two people can install themselves. Also people who buy whole truckloads.”

The Future of Soapstone Looks Green

The Future of Soapstone Looks Green

Alberene is paving the way for more sustainable building practices with soapstone. From their ecofriendly methods of quarrying to their product being used in LEED-certified buildings (a government-sponsored green building program), soapstone is creating its own niche in today’s greener homes. Besides being located in our very own backyard, Alberene is also within a 500-mile radius of many large metropolitan areas, making them highly accessible and considered a local product. Also, all of Alberene’s quarries are within 15 miles of their mill in Schuyler.

Some of Alberene’s soapstone blocks are reclaimed from when the company mined and miscalculated cutting the soapstone blocks 80 years ago. Using these existing quarries reduces extra blasting and processing. Alberene also pumps water from a hydroelectric dam that is situated on the Rockfish River. They pump the water from the dam to a water tank on the highest point in Schuyler, then gravity drains the water into the mill where the soapstone is processed. McQuarry says that the waste water “contains nothing harmful to the environment” and filters naturally into the ground.

“We are a local product, somewhat of a green product, and have a historical part in it,” McQuarry says. “And a lot of people seem to like that.”

Thank you to Alberene Soapstone Company for providing photos for this article.